- U.S.-Chinese relations have become more challenging, with a potential big impact on the global economy.

- The focus has moved from trade and tariff issues to a much broader conflict centering on technological leadership and reduced economic interdependence.

- Geopolitical issues are involved as well, as tech dominance means military dominance.

Introduction

China is facing unprecedented global challenges. Since the new U.S. government took over, initial hopes of an improvement in bilateral relations have faded and it seems the potential fields of conflict are on the rise. The focus on the bilateral trade relationship has given way to a much more profound conflict over future technological and geopolitical leadership. The U.S. now sees China as a strategic competitor.[1] Along with deteriorating bilateral relations with the U.S., China is facing increasing pressure globally on human-rights violations, regional military actions and other issues. A key trigger for Western countries' changed attitude was the implementation of the Hong Kong security law in mid-2020 and more recently human-rights issues related to the Muslim Uyghur minority. At the G7 meeting in the spring the U.S. called for the major democracies to unite against the rise of autocracies and the Build Back Better World (B3W)[2] initiative was introduced as a response to China's Belt and Road Initiative, which focuses on increasing China’s influence in developing countries through the development of large infrastructure projects.

Europe is more reluctant to confront China in a systematic way as it sees it as a necessary economic partner and not as a strategic threat, but Europe is fully on board with sanctions on human-rights violations. The Chinese-European Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), has been put on hold. This was after it had been agreed in December 2020 after eight years of negotiations and originally expected to be ratified by the necessary number of EU member states by end of this year. This was a reaction to Chinese countermeasures against members of the European Parliament after the EU decided to invoke sanctions on human-rights violations. Still, Germany and France are interested in maintaining a dialogue with China and getting the investment deal through. A potential further obstacle for China is a new law in Germany (and similar laws may be passed at EU level) to make German or European firms responsible for any co-operation with Chinese counterparts using forced labor schemes or failing to adhere to other labor laws.

1/ It started with a trade war…

The U.S. and China agreed that by the end of 2021 China should increase its purchases of certain U.S. goods and services by a combined 200 billion U.S. dollars above the 2017 baseline levels.

Focusing on the bilateral deficit with China is a lose-lose game

The previous U.S. administration under President Donald Trump embarked on a three-year trade conflict which focused on the large and rising U.S. bilateral trade deficit with China. During this time the bilateral average tariff rate rose notably for both sides, from single-digit rates to over 20%. Tariffs were frozen at these elevated levels when, on February 14, 2020, a truce was agreed: the so-called 'Phase-One agreement'. The U.S. and China agreed that by the end of 2021 China should increase its purchases of certain U.S. goods and services by a combined 200 billion U.S. dollars above the 2017 baseline levels. However, neither last year nor, so far, this year has China complied with the promised amount of purchases. By May 2021 China's purchases of all products covered in the treaty had amounted to only 62% of the year-to-date target.[3]

The U.S. bilateral trade deficit with China fell in 2019 and at the beginning of 2020 but has increased again during the pandemic as Covid-related demand for medical gear and electronic goods for remote work soared. China's exports of medical products nearly tripled in 2020, with 105 billion U.S. dollars in goods shipped.[4]

China: Share of global exports continues to rise

And yet the total current-account surplus of China (with all countries) has shown a marked downward trend since its peak in 2008 at more than 10% of gross domestic product (GDP) to roughly 2% of GDP now. In particular, Chinese imports from developing countries in Asia have picked up in recent years.

Article continues on next page..

2/ …and has shifted to technology and human rights

Non-tariff barriers and restrictions on China

While the punitive tariffs placed on China have not materially affected the Chinese economy,[5] the shift to non-tariff measures, in particular U.S. export restrictions preventing Chinese telecom and communication companies from importing vital silicon chips, have had a more severe impact.

In August 2018, President Trump banned the equipment of two large Chinese telecommunication firms from being used by the U.S. federal government, citing security concerns. Furthermore, in May 2019, the Department of Commerce added a Chinese telco giant and 70 of its foreign subsidiaries and affiliates to a list that restricts U.S. companies from selling goods to them without a government license. The lack of access to U.S. technology, makes it difficult for them to design and produce their own chips.

Human-rights violations increasingly have economic implications, too

China’s relationship with the rest of the world has not only deteriorated on security issues, but also on intellectual-property-rights violations and uneven market access. Over the past year, the question of human-rights violations has increasingly moved into focus.

One trigger was the June 2020 introduction of the Hong Kong security law. The U.S. introduced sanctions under the Hong Kong Autonomy Act in August 2020. Chief Executive Carrie Lam and ten other Hong Kong government officials were sanctioned by the U.S. Department of the Treasury under an executive order for undermining Hong Kong's autonomy. On December 7, 2020, the U.S. Department of the Treasury imposed sanctions on all the 14 Vice Chairpersons of the National People's Congress of China for undermining Hong Kong's autonomy and restricting freedom of expression or assembly.

These sanctions were directed at politicians involved with the issue; they were banned from traveling to the U.S. or Europe, which introduced similar sanctions.

More recently, new U.S. sanctions on China were introduced, with direct economic implications. U.S. measures on human-rights violations and forced-labor schemes in the Xinjiang region, which is populated by Uyghurs, have stepped up recently. In a first move, in June, the U.S. banned imports of solar-panel components from Xinjiang and on July 14 the U.S. Senate voted to pass legislation to widen the ban to include all imports of goods from the region. Passed by unanimous consent in the Senate, the bipartisan measure intends to shift the burden of proof to importers, while the current rule bans goods only if there is reasonable evidence of forced labor. The bill must pass through the House of Representatives before it can be sent to the White House for President Joe Biden to sign into law.

China has reacted to the various new restrictions and sanctions with the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law which establishes a legal basis for counter sanctions on foreign individuals or entities involved in applying sanctions on China. To what extent this law may be put into practice remains an open question.

Article continues on next page..

3/ Regional political relations are becoming more complicated, too

Last but not least, tensions have risen in the South China Sea with various neighbors of China as well as with Taiwan. In addition, China is in a trade and tariff conflict with Australia.

Not only are the economic links between Taiwan and China strong, but Taiwan also remains important for the global economy and financial markets. It is strategically located close to the Chinese coast and has a crucial role in Asian tech supply chains as well as with regards to tech integration between the U.S., Europe and Asia. Any conflict between China and Taiwan could have a painful impact on the global tech supply chain. Taiwan’s biggest semiconductor firm controls 84% of the market for specific high-end chips. It produces the smallest, most efficient circuits on which the products and services of the world’s biggest technology brands rely. Demand for these sophisticated chips is surging thanks to the expansion of fast communication networks and cloud computing.[6]

4/ The battle becomes technological

Producing high-end (new-generation) chips and fostering self-sufficiency are the focus.

The strategic approaches for both countries have similarities

Looking into the medium-term strategic plans of the U.S. and China, one finds striking similarities. Both countries embark on an unprecedented innovation and tech boost. In a nutshell, both countries are aiming for technological leadership, seeking to set future standards in new technologies via the first-mover advantage, reach self-sustainability in crucial inputs, and achieve cyber sovereignty.

The U.S. and China are therefore developing their high-end technology sectors and stimulating innovation in an unprecedented way, the U.S. via its Innovation and Competition Act (USICA), and China through programs in its fourteenth five-year plan, for 2021-2025. Global leadership in the big technological trends of the future is the ultimate goal: Artificial Intelligence, 5G, autonomous driving, electrical cars, the green economy, robots and the internet of things. For these purposes, producing high-end (new-generation) chips and fostering self-sufficiency are the focus.

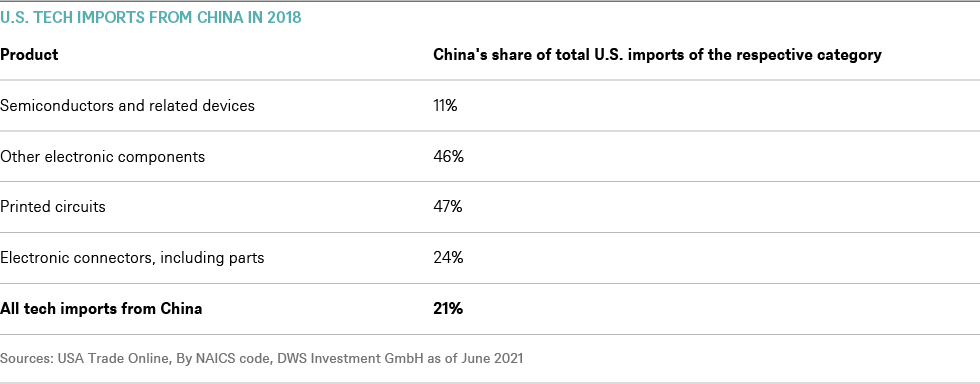

So far, the global tech supply chains are working according to competitive advantages. China produces simple, but also increasingly complex, chips and other tech goods with a big price advantage compared to the U.S. and the rest of the world. This has kept global goods prices low. But China relies on U.S. inputs when it comes to the cutting edge in technological progress – for example, chips for quantum computers. And as the supply-chain shortages caused by the pandemic and the now three-year-old U.S.-China trade and tech conflict reveal, it comes with a cost: mutual inter-dependence. With the U.S. now seeing China as a long-term strategic rival, China is even more keen to foster its own technological strength.

Technological development remains vital for China's future economic growth path because boosting productivity is critical to sustaining economic growth, as demographics become more difficult, with an aging population.

China's 2021-2025 plan focuses on an aging population and tougher geopolitics

China's new 2021-25 five-year plan (FYP) reflects its new challenges. It marks the beginning of a transition from a high-middle-income country[7] to a developed one – the 2035 socialist modernization agenda. The main targets aim to boost domestic consumption, sustain investment in targeted areas such as innovation and green development (with carbon neutrality by 2060) and to partially open up capital markets.

Technological development remains vital for China's future economic growth path because boosting productivity is critical to sustaining economic growth, as demographics become more difficult, with an aging population. Technological independence and supply-chain security have also become an urgent goal in light of increasingly difficult relations with the U.S. and other countries. A cornerstone of the FYP is innovation, with tech self-reliance and digitalization a top priority. China plans to increase research and development (R&D) spending by more than 7% per year[8], enhance intellectual-property-rights protection, offer more market incentives to researchers and encourage corporate R&D spending with tax subsidies. More investment is also planned in frontier tech areas, fundamental research, advanced manufacturing and new infrastructure, for 5G artificial intelligence (AI) and the internet of things as well as the construction of big data centers.

U.S. Innovation and Competition Act (USICA)

On June 9 the U.S. Senate passed USICA, a 250-billion-dollar bill aimed at countering China's technological and geopolitical ambitions. The bill provides 52 billion dollars to fund semiconductor research, design and manufacturing initiatives, with the aim of bringing back chip production to the U.S. and addressing supply-chain vulnerabilities. It includes additional support for new-energy vehicle batteries, robotics, 5G, quantum computing and AI. The plan covers critical products from circuits to medicine to chips.

Bringing back chip production to the United States is a central part of the initiative as the global share of semiconductors and microelectronics manufactured in the U.S. has fallen in recent decades, from 37% of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity in 1990 to just 12% today.[9] Foreign competitors like South Korea, Taiwan and now China are investing heavily in order to dominate the industry. The U.S. plan also provides support for private-sector R&D spending.

In order to prepare for strategic competition, addressing China's alleged intellectual-property theft and large-scale state subsidies for Chinese companies are also on the agenda. Furthermore, there is pressure for intensified use of existing sanctions against perceived Chinese violations – of human rights, cyber espionage, illicit trade with North Korea, fentanyl production and distribution and other issues – and providing for broad new mandatory sanctions.

Bringing back chip production to the United States is a central part of the initiative as the global share of semiconductors and microelectronics manufactured in the U.S. has fallen in recent decades.

Article continues on next page..

5/ What to expect? Decoupling could lead to big costs for all

The direct and indirect costs of decoupling

Recent history and, in particular, supply shortages of sensitive products (such as medical gear) during the pandemic, has shifted the focus to the substantial risks and downsides to a globalized world with highly integrated economies, financial markets and tech supply chains. While undoubtedly dependence can create serious vulnerabilities, the opposite trend, economic and financial-market decoupling, has its costs as well. The obvious effects are foregone corporate revenues, reduced potential GDP growth and higher price pressures from reshoring[10] (the last thing we need currently).

The top-down macroeconomic impact may be somewhat limited as China and the U.S. have large domestic markets and net exports have relatively little weight in GDP growth in both countries. Furthermore, the link between stock-market movements and the economy is much weaker in China than in the U.S. because Chinese private wealth is less invested in the stock market and more in real estate compared to the U.S.

Select corporates, however, could be vulnerable in a decoupling scenario. Corporate revenues from China in the U.S. are only a small portion of U.S. companies' total foreign revenue (see Chart), but in certain sectors the exposure is considerably higher. In the U.S., semiconductors & semiconductor equipment have the highest exposure to China, where they earn 29% of their revenues. Automobiles and components (16%), technology hardware & equipment (15%), energy (14%), consumer durables & apparel (11%) also have sizeable exposure. In China's A-shares market, the IT sector is most exposed, as 18% of earnings in this sector stem from the United States.

Via the various channels the estimated costs of decoupling would be significant. The study analyzes four scenarios taking into account the different channels these would affect: trade, assuming 25% tariffs would be placed on all traded goods; investment flows, assuming U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) in China falls by 50%; U.S. services exports, assuming the absence of Chinese students and tourists as well as R&D spending, assuming diminished access to Chinese talent and science.

Overall, the costs of even a partial U.S.-China decoupling scenario could amount to hundreds of billions of U.S. dollars annually, as the study cited above concludes. To this would be added other, difficult to quantify costs stemming from the loss of competitive advantage, loss of power to set global standards and supply-chain replacement costs, among others.

Return to a multilateral approach a distant possibility

There are other fields where U.S.-Chinese co-operation is very important. The world’s superpowers need to co-operate on ecological topics and climate-change solutions as well as the global pandemic, to name only the most current issues. The security risk from rising nuclear powers also cannot be ignored. For China's Asian neighbors, choosing sides is a no-win game. China is the main trading partner for most Asian countries. The region's financial markets are deeply integrated. While suspicion about China and its economic and military power is rising, the level of economic integration is profound. Despite political tensions, formation of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which will be the world's biggest trade area, was signed off in November 2020.[11] This was a remarkable success: for the first time the economic giants and fierce competitors, China, Japan and South Korea, will share the same free-trade area with Australia, New Zealand and 10 ASEAN countries. But the financial-market links with the U.S. and the complex nature of the Asian tech supply chain, itself closely linked to the U.S., mean that U.S.-Chinese co-operation remains fundamentally important. Any forced choice between the U.S. and China would be negative for most ASEAN countries.

Though there is a clear risk of further deterioration in global relations, there is also a distant possibility of a return to a more multilateral approach. China's President Xi Jinping surprised everyone when he announced at the virtual Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in November 2020 that China would actively consider joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) trade agreement.[12] After the United States withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017, the deal was salvaged under Japan's leadership with the remaining key members either dropping or compromising on some sensitive items in the final agreement. If China were to join this ambitious project, a major step towards a path back to multilateral co-operation could be the consequence. There is, however, no guarantee that China would be admitted if it did want to join. It would have to agree to all the provisions already in the deal, such as guidelines on labor rights, state-owned enterprises, government subsidies, e-commerce and cross-border data transfer. And some U.S. allies, such as Australia, might still not allow China to join.

Article continues on next page..

Conclusion

A fight for leadership to which the rest of the world must respond

- A new dimension. The deterioration in U.S.-China relations began as a trade and tariff conflict 4 years ago but has now become a much more complex issue. It centers around differences in the political and economic systems, geopolitical issues, human rights and the strategic competition for technological leadership.

- No quick solution. While recently some direct talks have begun between China and the U.S. on crucial issues, no breakthroughs are expected anytime soon. The current restrictive U.S. approach to Chinese firms is now more systematic (compared to 2017-20) and the measures and sanctions are, if anything, more severe. Furthermore, the political calendar in 2022, with the U.S. mid-term elections and the Chinese Communist Party’s 20th Party Congress both taking place in the fall of 2022, means concessions are unlikely, with both sides as committed as ever to their own tech champions and national projects.

- Technological competition broadens, Europe at risk of falling behind. The strategic competition between two economic superpowers poses both risks and opportunities. It is likely to trigger rapid and comprehensive technological changes on both sides. Other countries are also fostering their technological competitiveness. South Korea, for example, plans to spend 144 billion U.S. dollars to create 1,901,000 jobs by 2025. The plan focuses on a Digital New Deal and Green New Deal and on ten key projects ranging from green mobility to smart healthcare.[13] Europe needs to take care not to fall further behind. This is even more important as ongoing economic and trade integration in Asia, and in particular the upcoming RCEP, will likely make Asia still more competitive.

- An economic de-coupling would trigger higher global goods prices and lower potential growth in the long run. The main risks stem from a potential escalation or further deterioration in U.S.-China relations, potentially causing substantial damage to Asian and global technology supply chains. Should decisions about production locations be defined by self-sustainability motivations or geopolitical issues rather than by economic rationale, the resulting lower efficiency and higher goods prices might not be immediate, but no less harmful to the global economy in the longer term.

- Last but not least, a comforting observation. Despite the abundance of bold rhetoric, restrictions and hurdles weighing on bilateral U.S.-China relations, the two economies have recently come closer in some areas. Bilateral trade is booming even though punitive tariffs from both sides remain in place. China has continued to increase its holdings of U.S. Treasuries. And, finally, there seems to be one important area where both sides are ready to co-operate: climate issues and the environment in general.