- Home »

- Insights »

- Global CIO View »

- Macro »

- China: downturn or u-turn?

- The slump in the real estate market is the nucleus of several of China's structural problems, which makes for a persistently bad news flow.

- We believe that Beijing will respond not with massive fiscal injections but with targeted structural reforms, especially to strengthen the private sector.

- Many headwinds will remain, the confidence crisis being the chief one. But we expect almost 5% growth this year and next year, because China's strengths have not disappeared overnight.

Growth worries instead of reopening party - China in the maelstrom of bad news

Reopening goes less smoothly than planned, real estate sector remains the big problem

The stream of negative news from China seems never-ending. Economic growth in the second quarter disappointed. For the first time since 2017, more investor money is flowing into Asia ex-China than into China itself.[1] In the conflict with the U.S., we see escalation rather than easing.[2] The stock and bond prices of many real estate developers have collapsed, in turn causing imbalances among other financial services providers.[3] In the shadow banking system, there are imbalances linked to the real estate market. And the yuan has lost nearly 8% of its value against the dollar since its high in mid-January.[4]

To address some of the problems the party leadership came up with a reform agenda announced on July 24. But the positive response to that fizzled out within a few weeks. The impression formed among large segments of the population since the end of the Covid restrictions has persisted: There is unlikely to be a strong boost for companies and consumers to stimulate the economy; the government's words are often not followed by deeds; and uncertainty will linger. In addition, government communication looks inadequate. Foreign observers have noticed this, too. The abrupt discontinuation of the data series showing high youth unemployment is an example. Parts of Western media might also be accused of inadequate communication, as currently all China press coverage seems to focus on negative developments. China retains significant strengths, in some high-tech industries, the size of its domestic market, the low indebtedness of private homeowners, low foreign debt and the growing service sector, for example.

Short-term challenges meet structural problems

On top of all this, there are the long-term challenges: the shrinking labor population; the consequences of U.S. measures to restrict shipments of technologically important products; the high debt levels of local governments and their financial vehicles; and the question of whether the leadership in Beijing is prepared to give the private sector and financial markets the leeway they need to establish themselves internationally, even in the higher-value sectors, and to allow the 'new economy' to gain in importance. The overarching challenge is presented by a government that is once again acting more centrally, which could prove to be detrimental.[5]

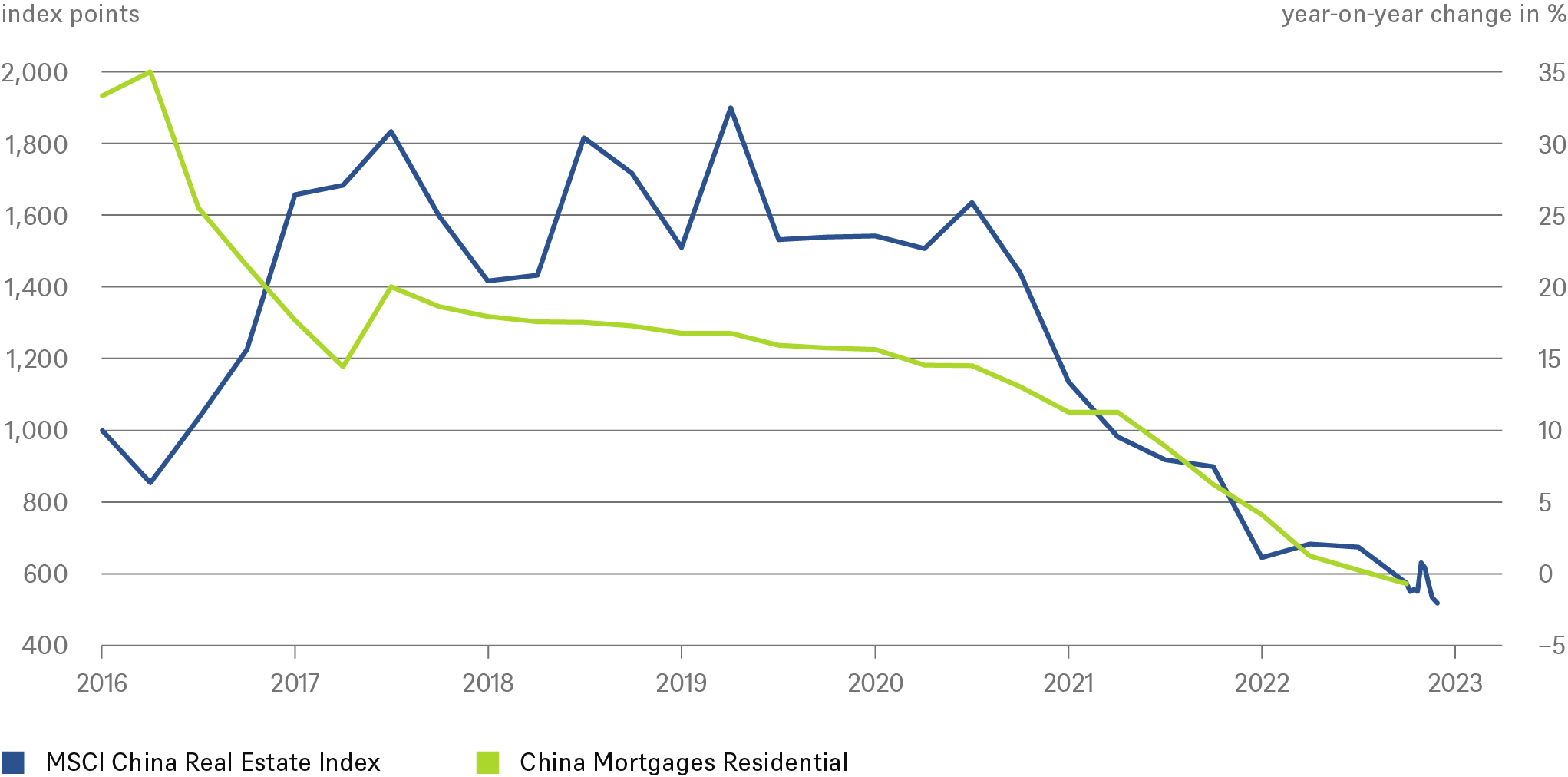

China's main problem at a glance: Real Estate

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH; as of 8/24/2023

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH; as of 8/24/2023

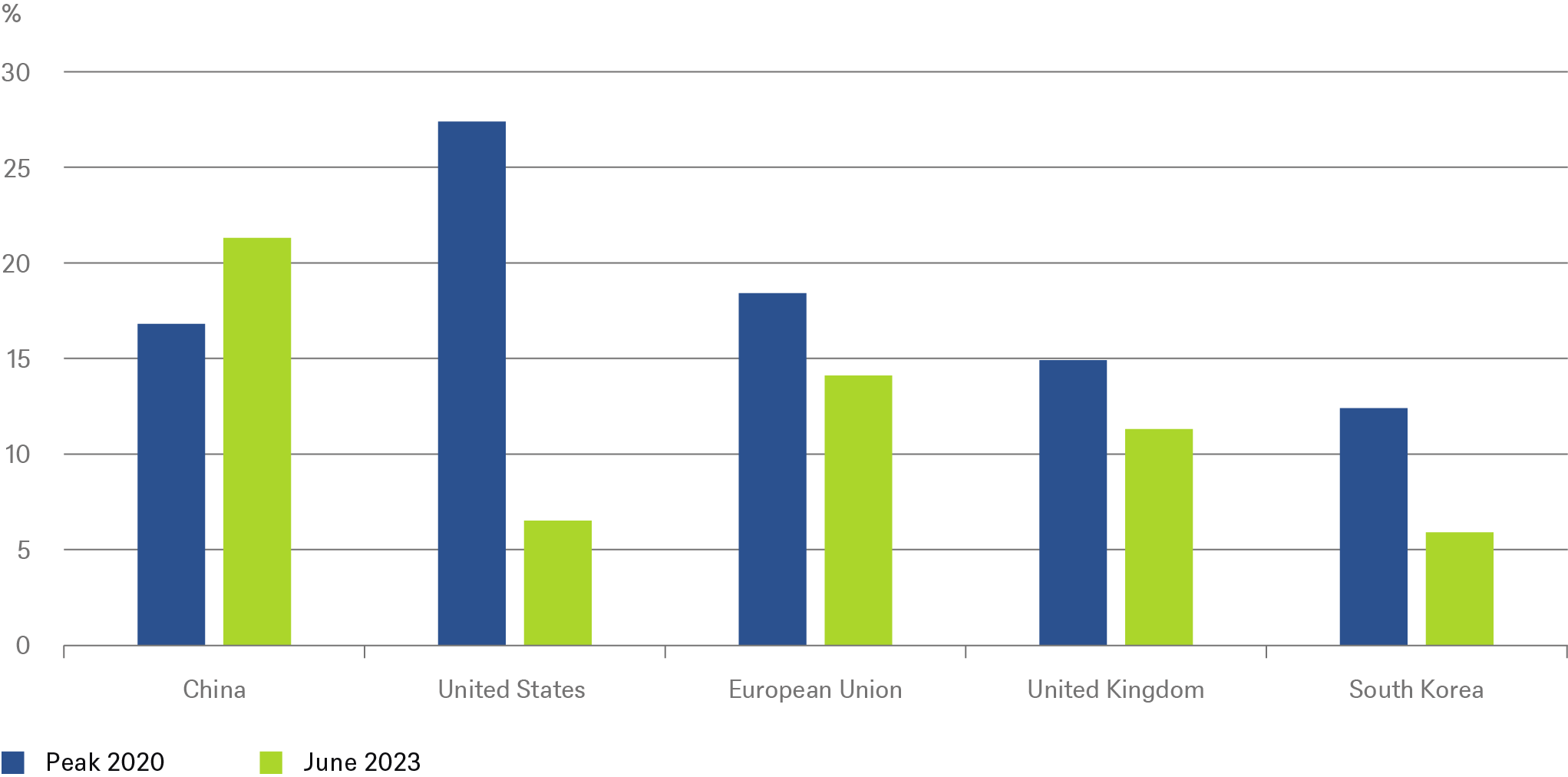

The Real Estate Sector as the Focal Point of Several Imbalances

In our opinion China's biggest challenge lies in the simultaneous imbalance of the real estate sector and two closely related sectors: the shadow banking system and the financing vehicles of the local authorities. Here there is a threat of a downward spiral, the timing of which is not foreseeable, especially as a large amount of finished and unfinished housing is clogging the market and further eroding confidence. The chart above shows the rise and fall of the listed real estate sector; the index has fallen by nearly three-quarters from its peak. In the real economy this is reflected in the rapid decline in mortgages for new homebuyers: it fell into negative territory year-on-year for the first time recently. There is no bottom in sight yet for either the real estate or mortgages time series.

We expect further negative headlines from this combination of real estate and financing and confidence crises, especially as we do not expect the government to be willing to try to reverse the trends with massive intervention. That may be a disappointment for investors, but we understand the government’s reticence: intervention could be counterproductive in the long run. Beijing wants to trim the volume and indebtedness of this sector back to a healthy level, even if this involves financial hardship for individual companies or property owners. Finding the right balance between selective, confidence-building reforms and measures to reduce systemic risks will be Beijing's major challenge in the coming months.

Confidence in party leadership shaken; but scale of challenges argues for pragmatic solutions

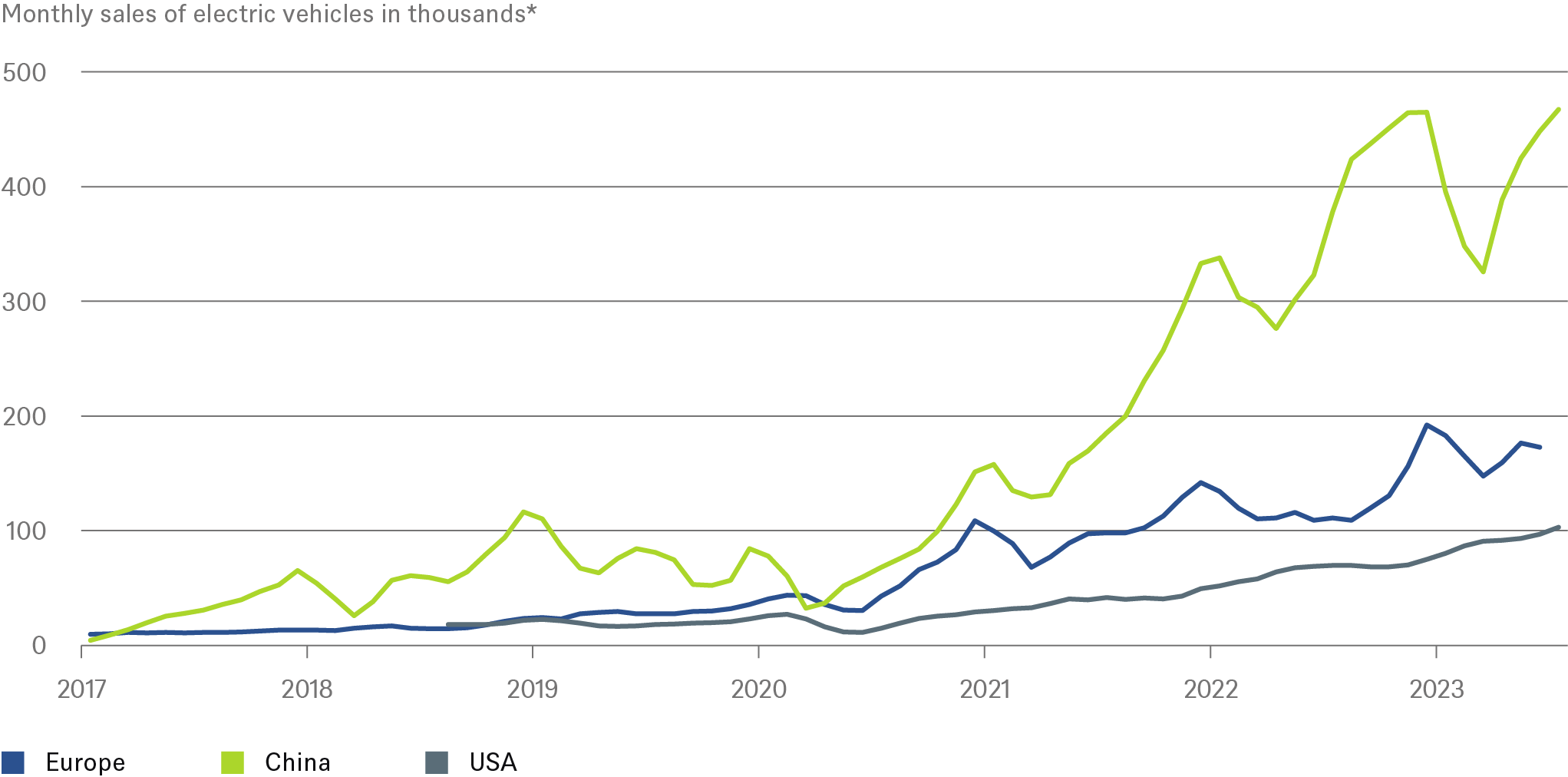

Next to the often-highlighted risks and negative developments in the country, we want to take a look in this study at China's strengths, to give a complete picture. The rapid increases in electric car sales, expansion of renewable energies and spread of state-of-the-art telecommunications infrastructure are just a few examples.

Where we perhaps differ most, however, from many skeptics is that we believe the party leadership is willing and able to take steps to address some of the country’s pressing problems. The likely measures include a focus on improving conditions for the private sector, the promotion of promising industries, and a reorganization of local government finances away from dependence on revenues from the property market. But we also understand the market’s skepticism that a party leadership that only recently trimmed the private sector and favored large state-owned enterprises[6] (SOE) will change its course. However, the many challenges the government faces mean it is probably aware of the need that there is no alternative to taking action. President Xi Jinping proved last year that he is capable of pragmatism when, due to pressure from the population, he ended the strict lockdown measures to contain Covid.

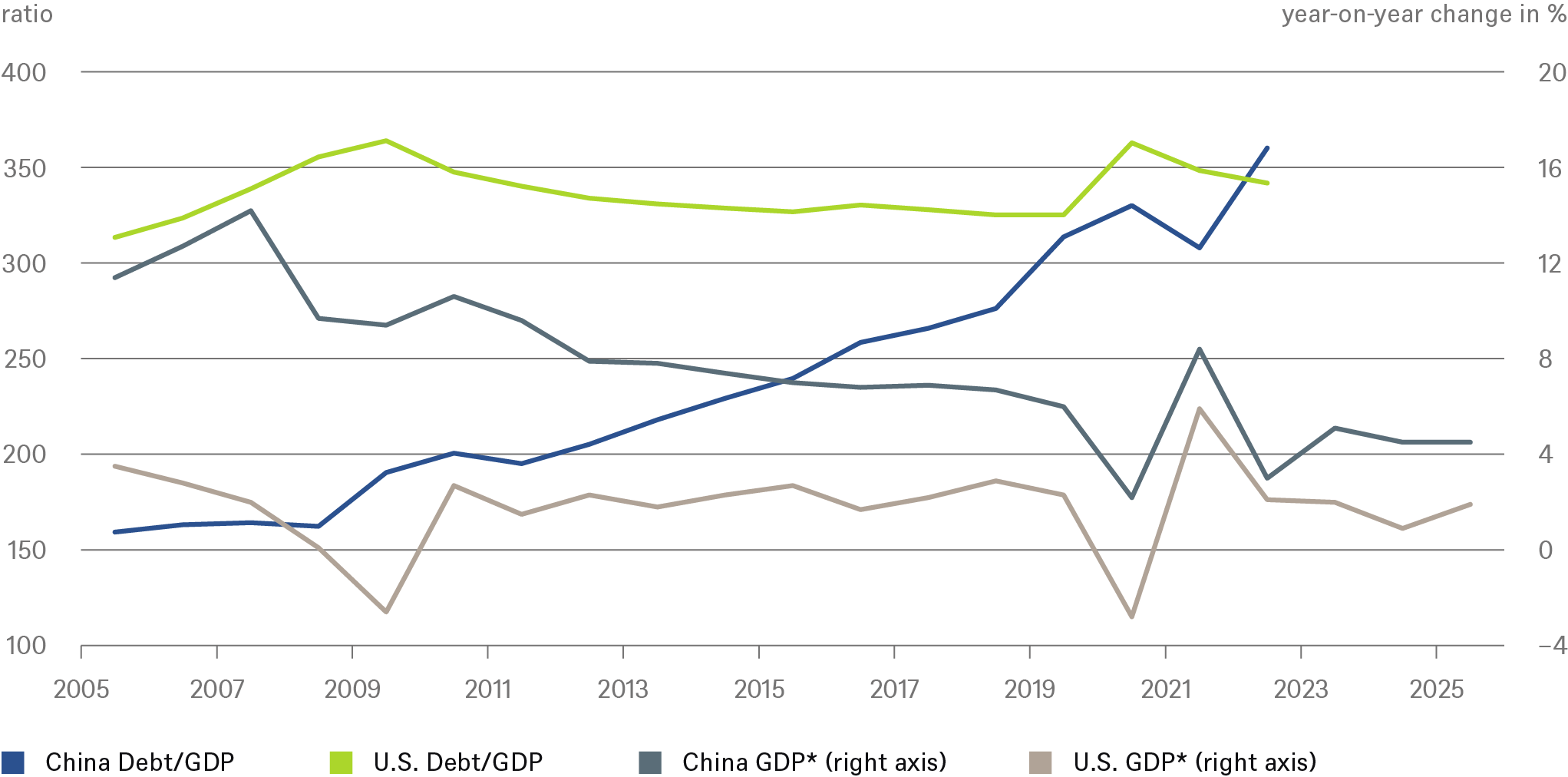

Growth rates are falling, debt is rising: China is converging with the United States

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., Haver Analytics, DWS Investment GmbH as of 8/28/23

* Bloomberg consensus forecasts for 2023-2025

1 / Reopening party remained only a flash in the pan

1.1 Where does China stand in the first post-Covid year?

Before we elaborate on the measures that Beijing is taking in order to address the problems, we look briefly at where the Chinese economy is now. A fairly strong first quarter raised hopes but was followed by a much weaker second quarter, and we fear the third quarter will not yet show any signs of recovery. The mood on the capital markets has deteriorated.

China's retail sector has not yet overcome the Covid slump

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH as of 8/24/23

The demand side of the economy is lagging. Households are hesitant to spend or are focusing on services, such as tourism, to which they were denied access for a long time. At the same time, they are saving even more. July and August trade figures confirm the negative trend: Imports are weakening and exports are suffering from weaker global demand. The chart above shows that nominal consumer spending has not yet approached its pre-Covid trend. Compared to the previous year, when Covid was still hampering the economy, growth in July was only 2.5%.

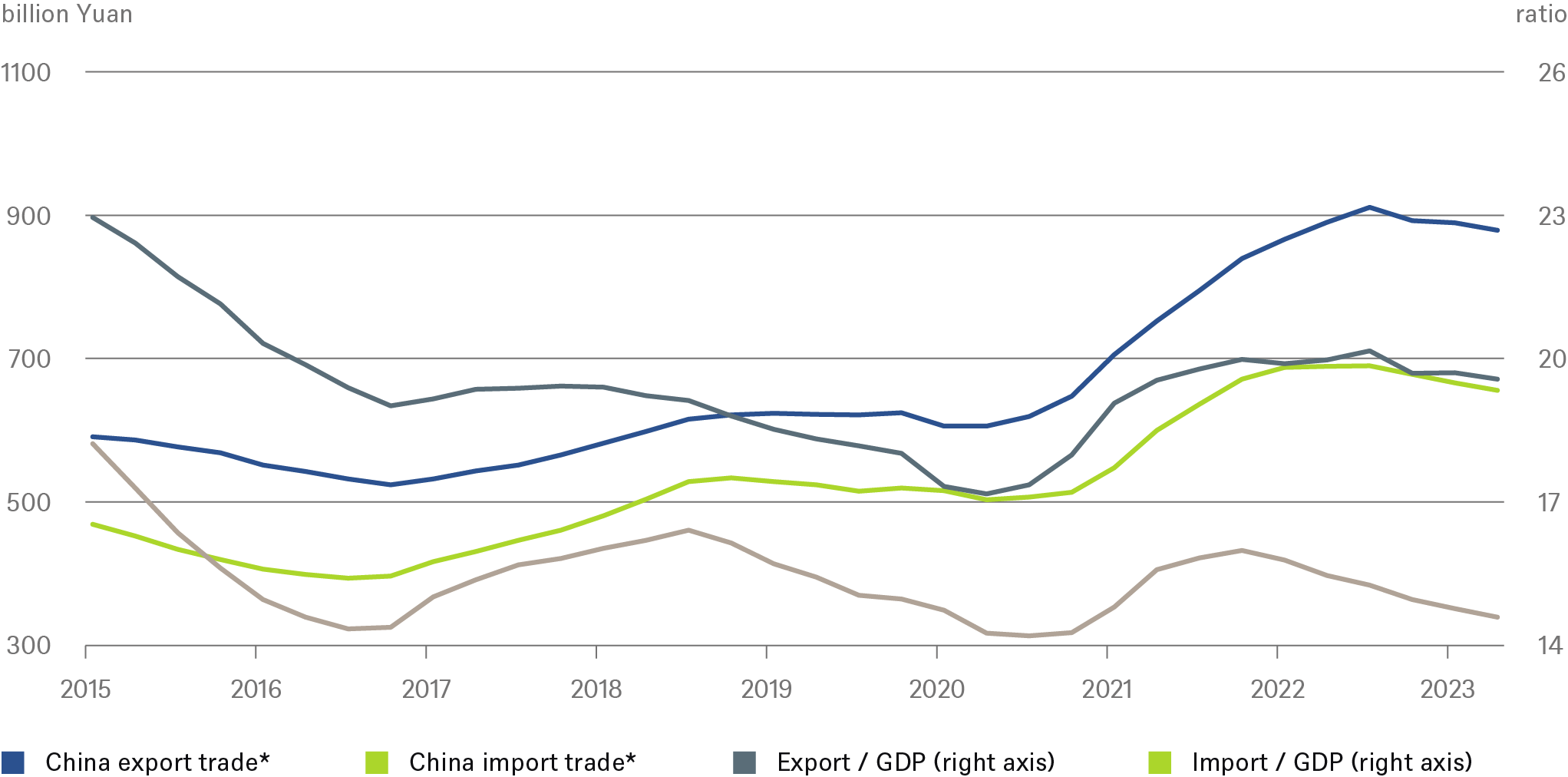

China imports and exports, quarterly

*4Q moving average

*4Q moving average

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH as of 8/24/23

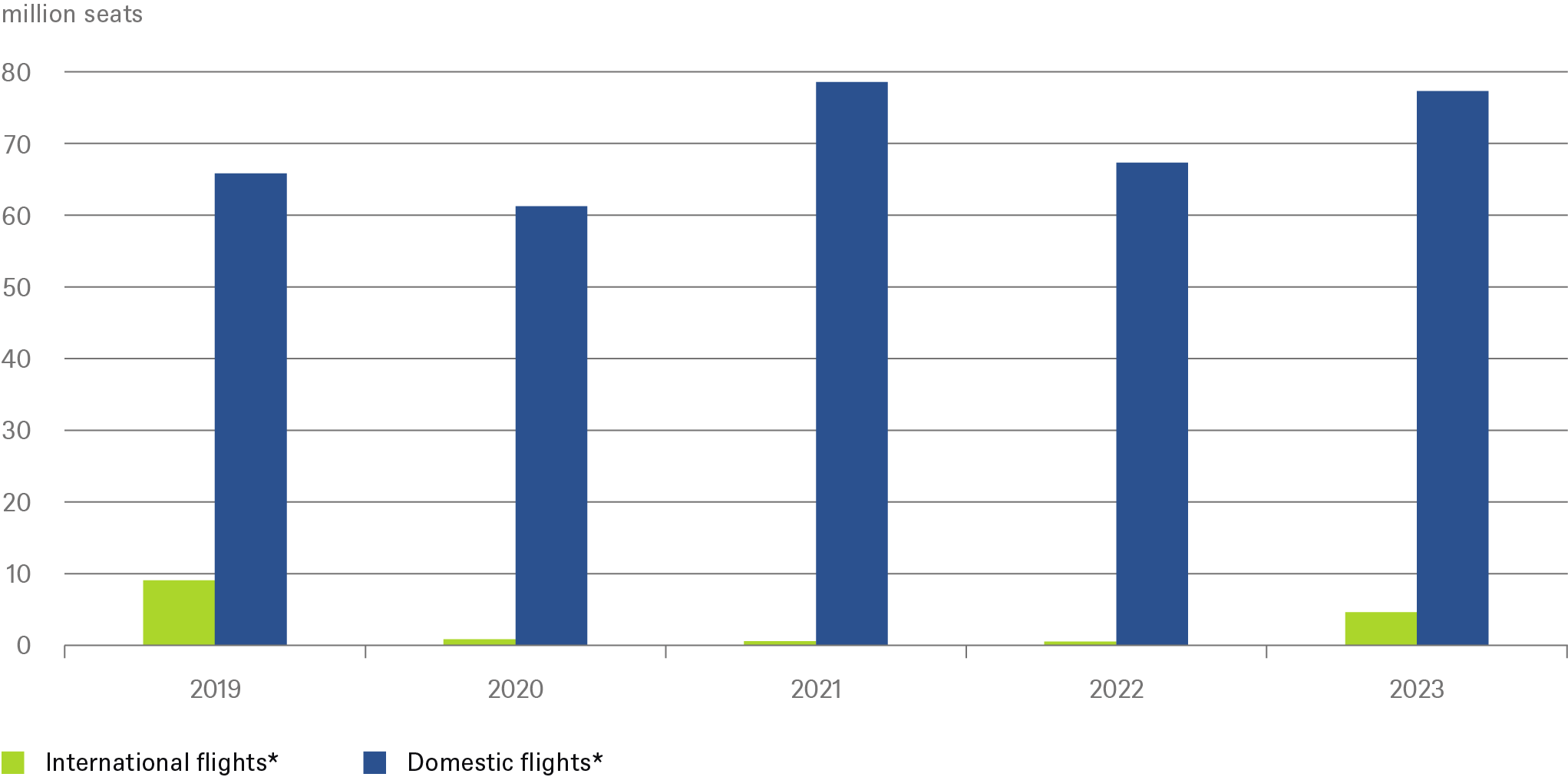

In the deterioration in international trade, structural changes are evident, along with the dislocations of the Covid years. The chart shows the absolute growth in imports and exports. Exports were boosted by global lockdowns and the demand created by people working from home.[7] This trend has reversed over the past year. In addition, the dispute with the U.S. has escalated, with Europe and other regions also imposing some export and import restrictions. The share of imports in Chinese Gross Domestic Products (GDP), which has been declining for some time, supports the theory that foreign countries are likely to benefit less from a Chinese recovery than in the past. But this decline reflects Beijing's goal of reducing dependence on foreign goods and strengthening domestic supply. China's more inward-looking recovery is also reflected in air travel, as the chart below shows. While the volume of domestic flights has already grown above the pre-Covid level, international flights, which in any case only account for around 5% of all flights, are at only half the pre-Covid level.

China's flights stay in the country

*Data for June of each year

Sources: Official Airline Guide (OAG), DWS Investment GmbH as of 7/25/23

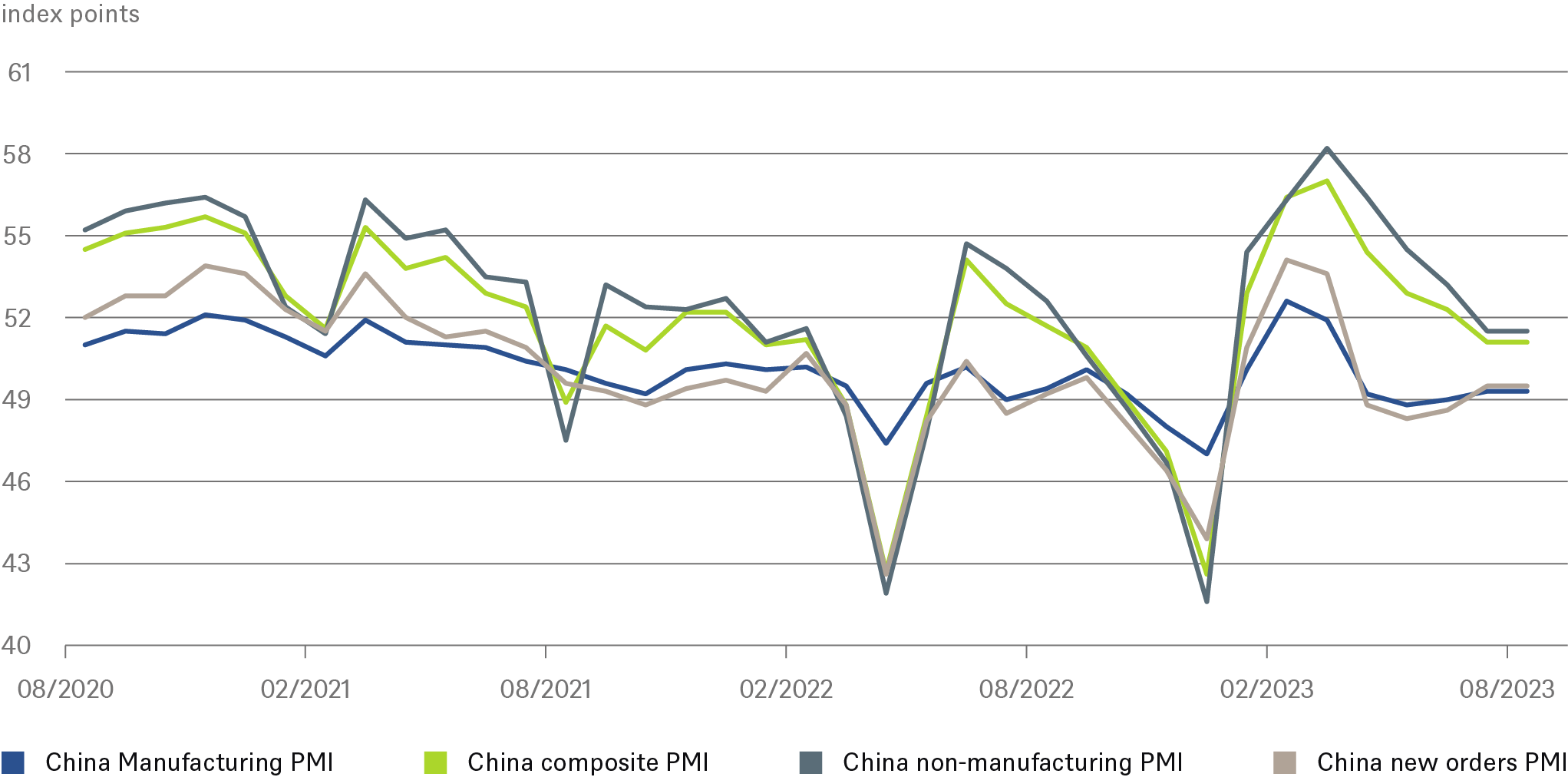

Despite these problems the Chinese economy is still growing quite fast. Growth is forecast to be almost 5% in the current year and to decline only slightly in the next two years – comfortably twice the rate of the U.S. But of course, the aforementioned risks in the real estate sector are potential threats to growth. The most important leading indicator, purchasing managers' indices (PMIs), have recently pointed downward.

The reopening euphoria has also quickly faded among purchasing managers

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH as of 8/24/23

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH as of 8/24/23

In the past, the state could often be relied upon to support economic momentum with fresh money and massive investment programs when needed. That this would no longer be the means of choice in the 2020s was already evident at the start of the Covid pandemic. And the current reticence to expand credit suggests that the government has indeed changed its approach.

China: Credit stimulus remains absent, youth unemployment remains high

* monthly, change year-over-year

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH as of 8/24/23

1.2 Short-term outlook

Following the presentation of the 2Q23 GDP figures, consensus estimates for the full year were cut from 5.5 to 5.2% within a few days.[8] In turn, growth forecasts for 2024 have been cut from 5.0 to 4.5% since early June[9] By lowering the growth target from (implicitly) 5.5% to "around 5%," Beijing's leadership, in our opinion, already gave itself more leeway in March, probably already suspecting that it would not be able to lift the economic growth rate this year. However, market sentiment deteriorated again with the publication of monthly data in August in which the publication of youth unemployment figures (see their rapid rise to over 20% in the chart above) was discontinued. This did nothing to build market confidence and some major brokerage houses have now reduced their GDP growth forecast to below 5%, which we consider realistic. In our main scenario we assume that already announced and new government measures should help economic growth to bottom out in the summer.

China: Economic indicators and forecasts |

||||||

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023f |

2024f |

|

|

Real GDP (% y/y) |

6.0 |

2.2 |

8.5 |

3.0 |

4.8 |

4.5 |

|

Private consumption (%, y/y) |

5.7 |

0.2 |

7.8 |

0.0 |

7.5 |

8.0 |

|

Fixed investment (%, y/y) |

3.9 |

4.2 |

3.8 |

3.5 |

2.8 |

3.1 |

|

Consumer prices (%, y/y, avg) |

2.9 |

2.4 |

0.9 |

2.0 |

0.5 |

2.0 |

|

Current account (% of GDP) |

1.0 |

1.9 |

1.8 |

2.3 |

1.5 |

1.0 |

|

General government fiscal balance * (% of GDP) |

-6.1 |

-9.7 |

-6.1 |

-7.5 |

-6.9 |

-6.4 |

|

Gross general government debt** (% of GDP) |

57.2 |

68.1 |

71.5 |

76.9 |

84.1 |

89.8 |

|

Urban unemployment rate (%, eop) |

5.2 |

5.2 |

5.1 |

5.5 |

5.3 |

5.1 |

|

Fiscal Balance refers to General Government Fiscal Deficit account IMF definition. Note: once new government support measures are known, fiscal deficit forecasts will likely be revised up, **Gross government debt from IMF economic outlook statistic // f= forecast. Forecasts are based on assumptions, estimates, views and hypothetical models or analyses, which might prove inaccurate or incorrect. Sources: Citi Research, DWS Investment GmbH as of August 2023 |

||||||

1.3 Is the real estate sector facing a lost decade?

The real estate sector is crucial for the current change in sentiment and also for the country's economic outlook. The sector plays a vital role in China for well-known reasons. Urbanization has been rapid, investments have been huge, and real estate has served as a retirement fund, given that social systems are inadequate and households distrust other capital investments. In a study the U.S.-based Peterson Institute[10] quotes two prominent academics, Kenneth Rogoff and Yuanchen Yang, who put the contribution of the real estate and construction sector to China's GDP at 26%. Real estate-related services alone accounted for 6.1% of GDP, in 2022 down from 7.2% a year earlier. The chart below shows above all that new construction remains very restrained, and the low turnover in the existing stock. It might also be that the price trend in the market, which has been negative since mid-2022, does not fully reflect the truth with a recent year-on-year decline of only -0.5%. The low level of transactions and Beijing's implicit instruction not to throw any apartments onto the market "below value" may have obscured the true picture.

China's real estate sector: stabilization at a low level?

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH as of 8/24/23

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH as of 8/24/23

Beijing's real estate policy can be divided into three time periods. First, until 2019: promotion of new construction, especially by local authorities, refinanced by land sales; fine-tuning via monetary policy and regulation by Beijing.

Second, the party leadership curbs speculation in the housing market severely, and thus also multiple home ownership, not least because this meant that ever larger segments of the population could no longer afford to buy their own homes. The main tool for this policy was the three red lines introduced in 2020 for construction companies and project developers.[11] Due to the high indebtedness of the sector, the consequences were drastic. Developers groaned under liquidity constraints. Many did not have enough liquidity to buy new land or start new projects, which was reflected in a 24% drop in housing starts in the first half of 2023. It could be said that the red lines served their purpose, releasing a lot of speculative air from the sector. But perhaps to too great an extent, especially since the pandemic, when the fundamental uncertainty felt by buyers, owners and potential buyers was exacerbated, leaving many apartments unfinished.

The third period has followed the loosening of the reins in the second half of 2022, when, for example, financing restrictions were eased and, according to the 11-point plan of November 2022, restrictions on property purchases were eased. But Beijing does not want to return to old times. We do not expect the real estate sector to regain the degree of importance it previously had in the economy, but rather to fall back to a 'healthy' level where supply and demand trends match.

To make this possible, however, Beijing will also have to push ahead with strengthened social security systems. At present, property is used by households as their safety net. According to figures from the People's Bank of China (PBoC), 96% of urban households live in their own homes and have 70% of their assets tied up in real estate. 41.5% of households own two or more homes.[12] Housing demand will fall from 15 million units in 2020 to 5 million units in 2050, according to OECD estimates.

For now, however, China is struggling with the real estate overhang and the financial problems of local governments and of capital market players that are directly connected to the sector. Part of the vicious circle is that 90% of apartments for sale were pre-financed by their buyers. With the (interest-free) payments, the project developers in turn financed further land purchases from the municipalities. This model suited everyone so long as prices rose and the apartments were completed. And prices did rise: The Economist calculated that house prices in Beijing increased tenfold between 1998 and 2021.[13] This meant that housing became four times more expensive when measured against (also) increasing disposable income. Beijing's apartments were twice as expensive relative to income as those in London.

2 / Beijing's reforms and aid packages

Even at the beginning of the Covid pandemic, it became clear that Beijing did not want to address the problems in the real estate sector with generous subsidies on the watering-can principle. And there are unlikely now to be any major programs to stimulate consumption. Not least because households’ uncertainty is also reflected in their adherence to high savings rates, even after the Covid pandemic.[14] Beijing is therefore focusing on structural reforms that should ultimately help to increase the willingness of the population and companies to consume and invest.

The current package intends, amongst other things, to partially correct individual points of the "Prosperity for All" agenda. Above all, the severe cuts in the real estate sector are to be amended. Furthermore, Beijing's preference for state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which are considered to be less efficient and dynamic, is also set to be revised.[15]

Some economic policy measures have been implemented since the economic turndown in Q2. In the real estate sector, given the threat of a wave of insolvencies, the main objective was to ease the restrictions introduced in 2020 to curb speculative activity and excess debt. Real estate developers regained access to financing, above all to reduce the destabilizingly high number of unfinished buildings. In late August the government announced steps to improve credit conditions for existing and new residential mortgages. In addition, a large number of decentralized measures were adopted to support particularly vulnerable consumers and smaller businesses. In addition, the state is boosting the economy with further infrastructure investments. However, as in the past 2-3 years, investments are being made less and less in classic infrastructure (roads and bridges) and more in digital infrastructure, as well as in measures to upgrade technology and further expand alternative energies.

One important measure that has at least been announced is the restructuring of provincial debt and its financing vehicles. Stabilization in this area could improve business and household sentiment and activity. To this end, it is expected that a comprehensive plan will be put in place to address the risks associated with local government debt. We might have seen a little step in this direction recently. Beijing seems to allow some regional governments to raise funds via the bond markets in order to restructure the debt of the most indebted LGFVs (local government financing vehicles).[16] Another reform, already announced, is to improve conditions for the private sector. Policymakers have promised to make it easier for private companies to make investments and establish regular channels of communication with businesses. Encouragement to enter new markets and take risks is not yet very concrete or helpful but could at least point the way forward, which would be a change from the policies of recent years. Given the great importance of the private sector as an employer, but also for its role in innovation and technical progress, the government has a great incentive to back up words with deeds this time.

3 / China's structural challenges

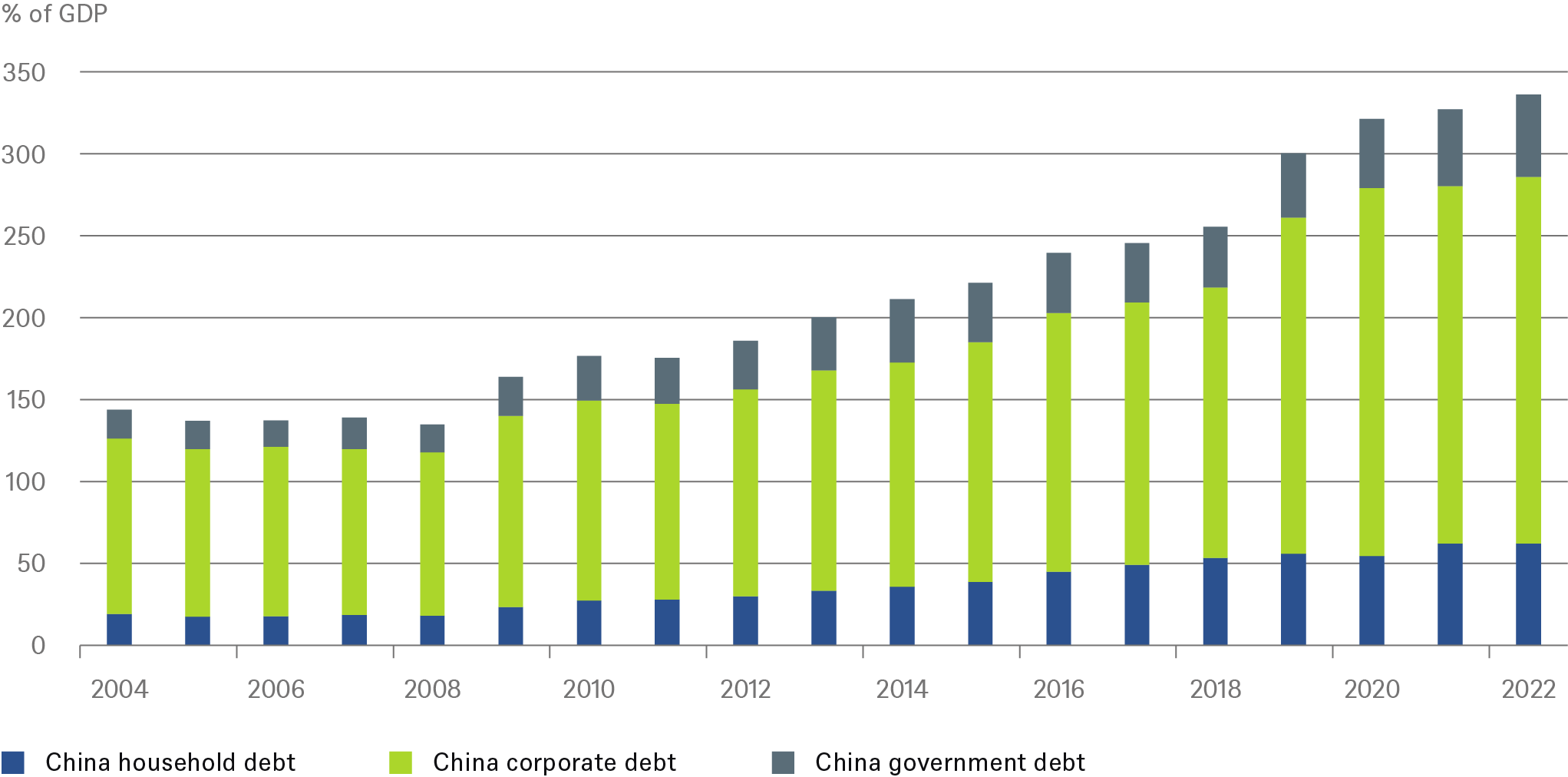

3.1 China's debt: almost like in the West

When does a country's total debt become destabilizing? There is no generally applicable indicator. Ultimately, whether a country (such as Japan) can afford a high level of debt in the long-term depends on the combination of the interest rate level and growth. Debt in China, especially provincial and corporate, has risen sharply in recent years. The chart below shows that total debt as percentage of GDP has doubled over the past decade. However, with an official public debt ratio of around 50%, China is not in a bad position, at least compared to many developed countries.

The comparison becomes somewhat more complicated, however, when one tries to take into account the debts for which the government is ultimately liable or willing to be liable. The debt shares also shift if the debts of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are reclassified. According to a September 2022 study[17]by S&P Global, SOEs accounted for 45% of non-financial corporate sector debt. The study also vividly sets out how poor the balance sheets and earnings power of the SOEs are; and that corporate debt, at 160% of GDP,[18]is not only about twice as high as in the U.S., but also scary in absolute terms – at USD 29 trillion, it is equivalent to the entire U.S. national debt.

Household, corporate and government debt as a percentage of GDP

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH as of 8/24/23

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH as of 8/24/23

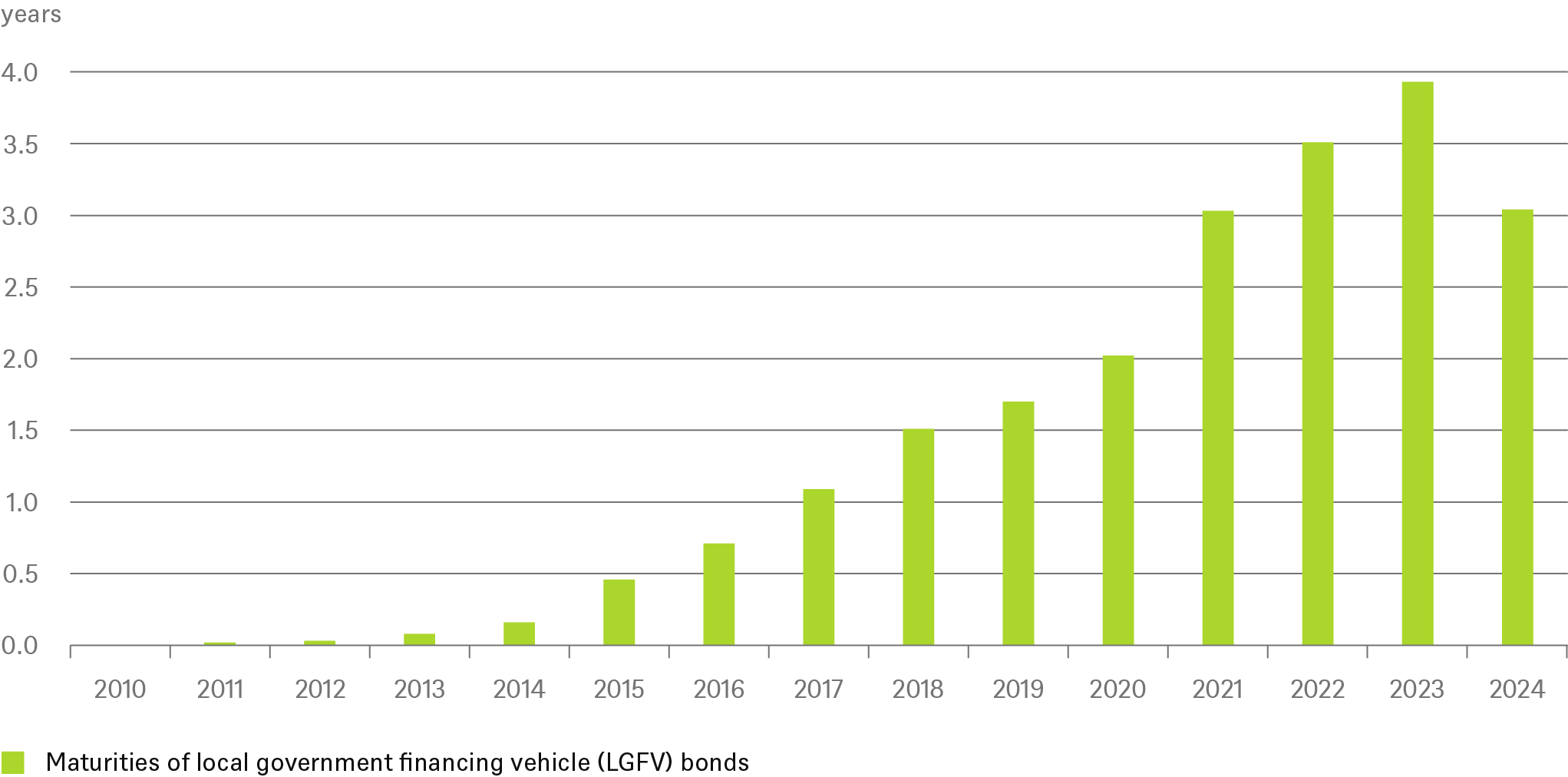

Municipal debt

The financial situation of China's local governments is structurally weak. Although they take in around 50% of total state revenues, they incur more than 80% of expenditures, with the difference regularly covered by transfers from the central government. In times of economic downturn, for example, the central government relies on local governments to invest in infrastructure, but without providing them with sufficient funds. Since local governments were not allowed to issue their own bonds before 2015, they have established financing companies – Local Government Finance Vehicles (LGFV) – to borrow from financial institutions and raise funds on the bond markets.

Repayment obligations from bond holdings of local real estate rising rapidly

Sources: Wind, Citi Research, May 2023, DWS Investment GmbH as of 5/01/23

Sources: Wind, Citi Research, May 2023, DWS Investment GmbH as of 5/01/23

According to estimates by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), outstanding LGFV debt amounts to around RMB 66 trillion[19](roughly half of China's nominal GDP), almost the same as central government debt. Scheduled bond repayments by local governments could reach a new high in 2023 (see chart). Declining tax revenues in the wake of the state's debt-reduction campaign and the impact of the Covid pandemic on the economy exacerbated concerns about local government debt. The likely further decline in revenue from land sales in 2023 (-27% in Q1 y/y) could further strain municipal funding balances, especially in provinces with weaker financing conditions.

Over the past decade, policymakers have already put in place a number of measures to prevent particularly vulnerable municipalities from defaulting. The toolbox will have to be enlarged in view of the pressing problems in the real estate sector, but we do not expect an all-encompassing restructuring that would involve granting the regions more autonomy. For the time being, the municipalities’ structural problems could become bigger rather than smaller. While land sales accounted for only 20% of local governments' total revenue in 2012, it was 30% at its peak in 2021 before falling to 24% in 2022. Land-related taxes accounted for another 7% of total revenues in 2022.[20] In addition to the current weakness in demand, local governments face another problem in the medium term: the amount of land available for sale is finite.

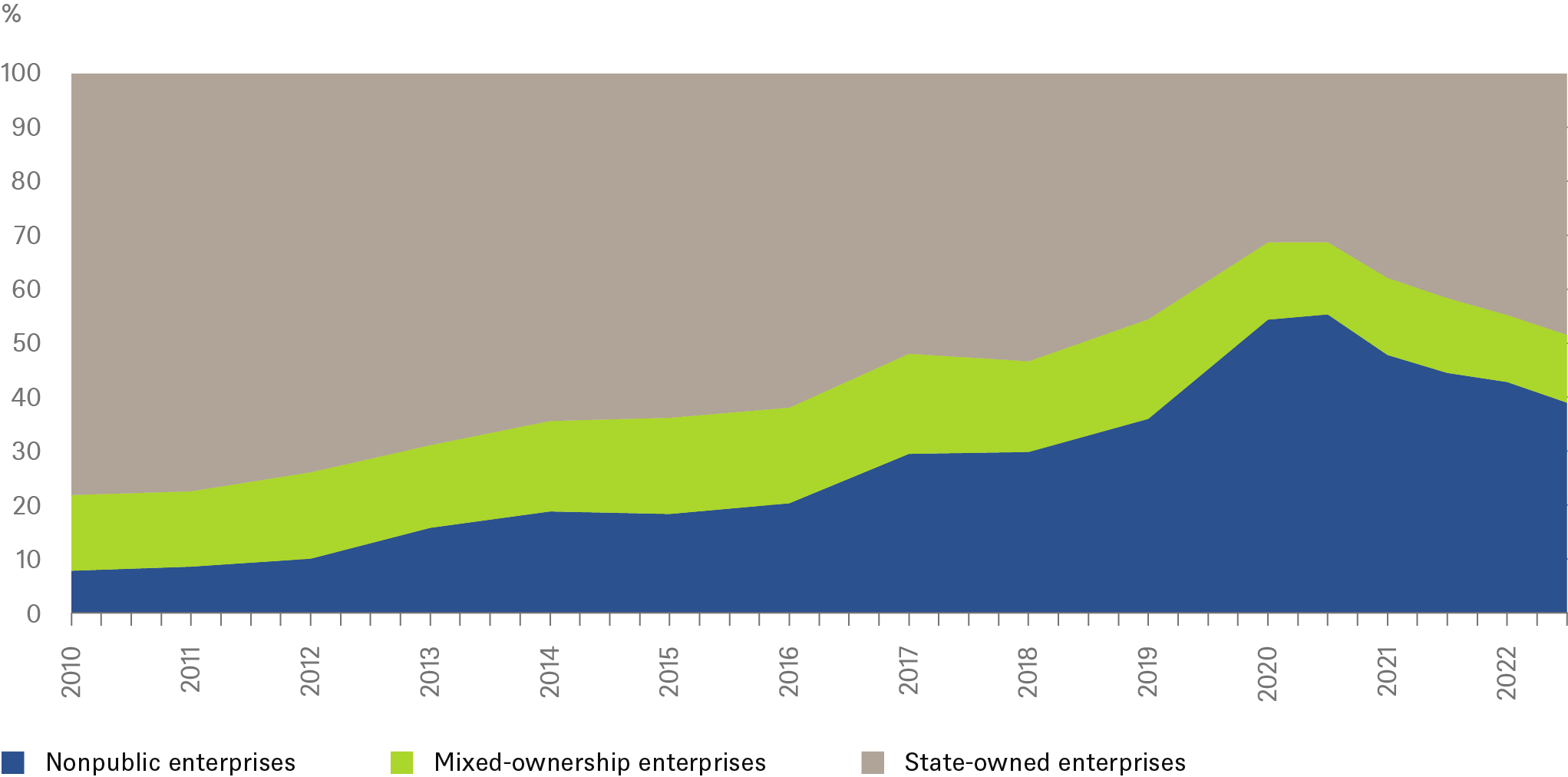

3.2 State-owned enterprises have recently regained weight

A look at the stock market underscores the recent resurgence in the importance of the SOEs: among the 100 largest listed companies, the SOEs'[21] share of market capitalization has risen from 31.2% to 48.4% since mid-2021.[22] The World Bank calculated in 2017 that they contributed around a quarter of GDP.[23] Now, to illustrate the importance of the private sector to China's development, government circulars like to cite the following figures: The private sector accounts for more than 60% of national GDP, more than 70% of technological progress, and more than 80% of urban jobs. China has more than 47 million registered private enterprises, the vast majority of which are small businesses, and more than 100 million self-employed workers. But these private sector companies have been hit hard by the pandemic, while some, such as Internet platform companies, real estate developers and private tutors, have also been affected by Beijing's regulatory campaigns.

Clear kink discernible in private-sector share in 2021

Concrete measures

A July 14 government document provided some details on how to promote the private sector; starting with key projects and industries previously organized primarily by the state that will now be opened up to private investment: transportation, water, clean energy, new infrastructure, digital industry and modern automated agriculture.

Furthermore, the plan addresses issues such as market access, fair competition, financing support, payment defaults and intellectual property rights and legal protection, among other things. The plan also envisages improving the current default prevention mechanism, which is often a matter of life and death for small businesses, and commits to creating a legal environment that ensures equal treatment for private entrepreneurs and protects their legitimate interests and rights. These are quite ambitious goals in our eyes.

An example of an industry where strong government support and private sector-oriented companies have developed tremendous momentum is the electric vehicle market. Amid intensifying global competition, economies of scale will play a major role, and here Beijing has put China’s companies in a very good starting position. Something similar can be seen in the battery sector (lithium) and in solar panels.

China drives away electrically from the rest of the world

*3-month moving average of battery electric vehicle sales

Sources: Various national sources as compiled by Exane BNP Paribas, DWS Investment GmbH as of 8/16/23

Prospects of success

Will the plan be implemented? Past experience casts doubt given that not long ago the government introduced measures that were to the detriment of private companies. What is different now, however, is the urgent needed to bolster the private sector, especially in view of its role in innovation and technological progress. The more China is cut off from key high-tech inputs from the U.S. and other G7 countries, the more important it is to become less dependent on them. Since the real estate sector, even though it may have stabilized after the slump, can never be the growth force it once was, and the labor force is shrinking, there is no other way to sustain economic growth, technological improvement and rising GDP per capita.

3.3 China's demographic outlook

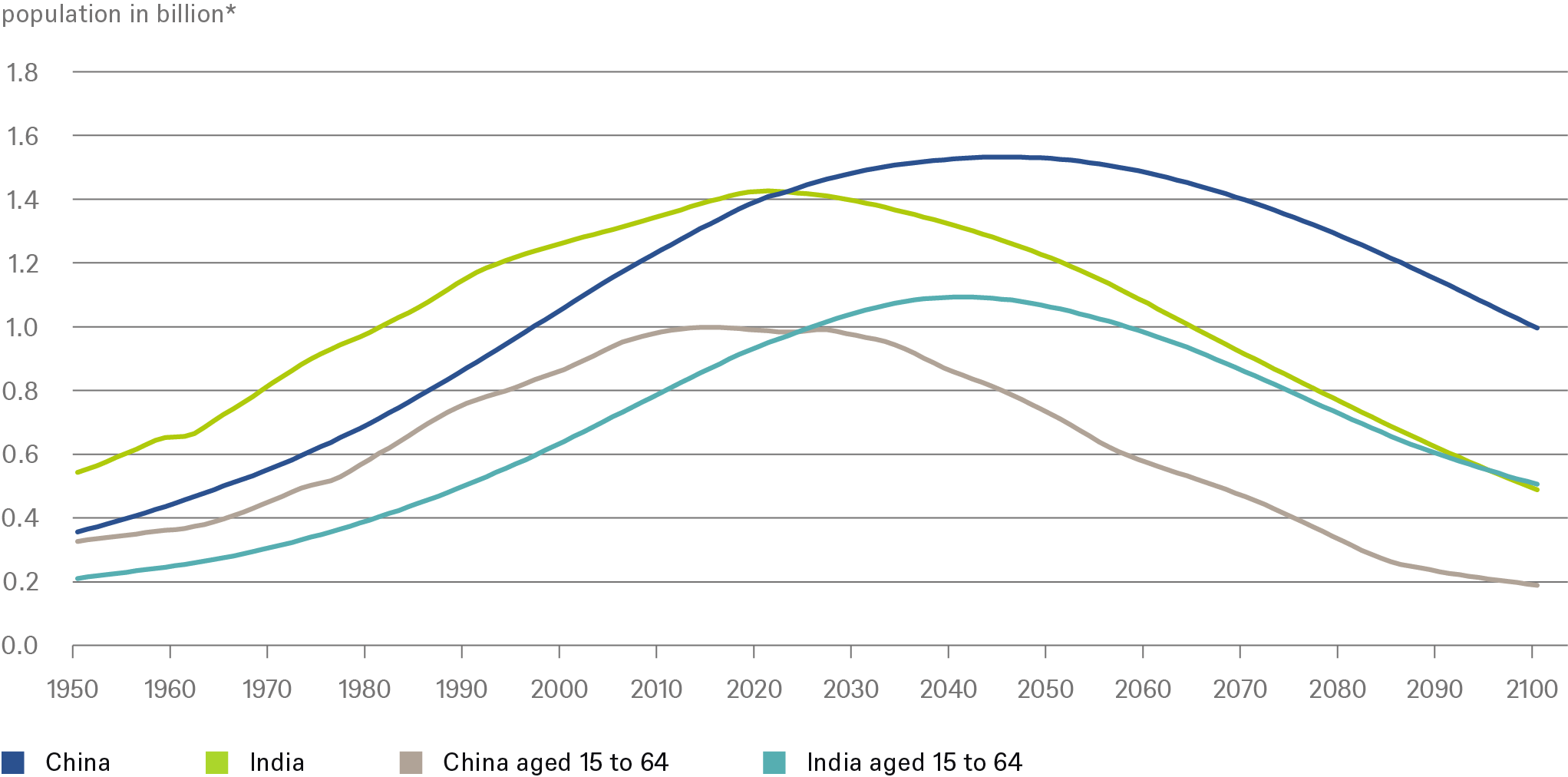

Demographic change is by its very nature long-term, but its impact is currently too powerful to be ignored in China. The decline in the total population probably began in the current decade but the shrinkage of the working-age population (15-64 years) started in the mid-2010s. India is not expected to reach these turning points for another quarter of a century, according to OECD estimates.

China's workable population is already shrinking

*Population from 1950 to 2100

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH as of 8/24/23

Like South Korea, China has been preparing for demographic aging for some time. The share of labor-intensive industries, which were still predominant 20 years ago and were based on the advantage of the country’s huge labor reserves, has been greatly reduced. The corresponding industries have migrated to Southeast Asia. Accordingly, wages have risen sharply over the past decade. Nevertheless, the continuing decline in the labor force poses a challenge per se. The negative effect on long-term potential growth can, however, be cushioned by some structural changes that are available to Beijing to stabilize total labor potential and increase labor productivity. The retirement age, currently 55 for women and 60 for men, could easily be raised. In addition, the rising degree of urbanization helps, as urban areas generate higher GDP per capita than rural areas. And there is still catch-up potential. Developed countries are on average 80% urbanized; China is only at just over 60%.

Enormous structural challenges

Nevertheless, the challenges remain formidable. The U.S. think tank, Foreign Policy,[24] has calculated that by 2040, more than 400 million people, or 28% of China's population, are expected to be older than 60. Accordingly, a 2019 study by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) warns that the National Social Security Fund (NSSF), established in 2000 to fund China's future pension obligations, is likely to be exhausted by 2035 unless appropriate countermeasures are taken to offset the burdens from the shrinking ratio of workers to pensioners.

What problem does high youth unemployment pose?

Having more than one-fifth of the 19- to 24-year-old population out of work is a headache for any government. All the more so when one-third of them are college graduates (2.5 million out of 6.3 million youth unemployed in the first quarter). The number skyrocketed during the pandemic and, unlike in other countries, did not fall again after the reopening. In absolute terms, however, this segment is likely to play only a minor role in the country's economic performance: it is about 6 million people compared to a labor force of around 500 million. The officially reported unemployment rate (including the 21% youth unemployment rate) is 5.25% overall.

In our opinion, one of the reasons for the high unemployment among graduates is an increasing orientation of students toward "soft" courses such as linguistics or literature, away from natural sciences and engineering. In addition, a large proportion of university graduates work in the private education sector, nationalized by Beijing two years ago. Most recently, the technology and communications sector has also sharply cut back on hiring. In addition, opportunities to study and work abroad have become more difficult. While the party leadership urges discipline, austerity and willingness, reports of frustrated young Chinese, uninterested in traditional industrial jobs, currently abound in Western media.[25]

Youth unemployment has not yet normalized even post-Covid in China

Sources: Citi Research, May 2023, DWS Investment GmbH as of 5/01/23

Sources: Citi Research, May 2023, DWS Investment GmbH as of 5/01/23

Possible solutions

The best remedy for (youth) unemployment is likely to remain economic growth.[26] The aforementioned strengthening of the private sector would help, as its innovations should also create more high-quality jobs. Finally, an education offensive that creates more incentives to study the subjects and qualifications that are in high demand could also help. The development of training opportunities for the urgently sought-after technically highly qualified industrial workers could provide further support.

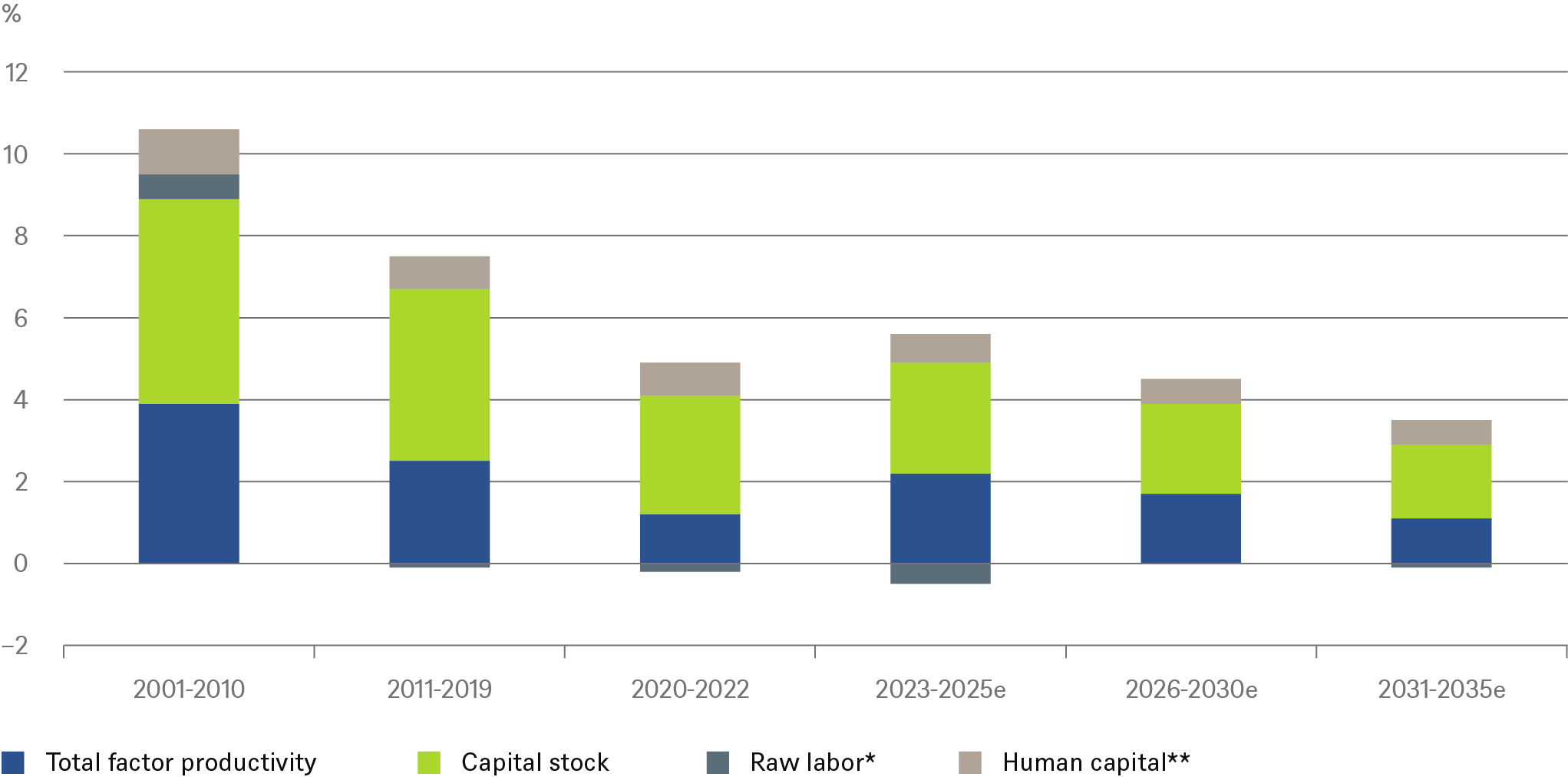

3.4 What about China's long-term growth potential?

It is not only the above-mentioned development of China's potential labor force that suggests China's growth potential is likely to decline in the long term. The country's more advanced stage of development also points to this. China's annual GDP growth potential is therefore likely to have fallen from 8% in the 20 years before the pandemic (2000-21) to about 4.5% currently, and is likely to fall gradually to 3.5 to 4% over the next decade.

Many consider this too optimistic, given the decline in the labor force and falling capital productivity. However, the better-known negative trends are offset by a number of countervailing trends: continued urbanization (from the current 60% to about 80% as in the U.S., Japan and Korea): and rising investment and consumption. According to the Bruegel Institute, the remaining scope for urbanization in China means that aging will hardly be reflected in lower growth until 2035 (see chart).

Expected development of China's potential growth

* Total hours worked ** Qualification of workforce e=estimates

Sources: BofA Global Research estimates, DWS Investment GmbH as of 7/25/23

Overall productivity can also be increased through sectoral shifts. Currently, agriculture still accounts for 23% of total employment (in high-income countries, the figure is only 3%). Increasing agricultural productivity could free up significant amounts of labor for other, more productive sectors. Of course, other sectors can also benefit from technological progress, which should help increase overall productivity. Digitization, a priority for years, and the expansion of advanced telecommunications infrastructure, might also be mentioned here, as both are necessary prerequisites for the introduction and application of Artificial intelligence (AI)-supported models and processes.

4 / China and the world – dancing at a safe distance

4.1 Is the tension with the U.S. going to escalate further?

China’s conflict with the U.S. can no longer be dismissed as political saber rattling or domestically motivated election campaign propaganda. Sanctions are becoming increasingly varied and concrete. The U.S. is pursuing the goal of slowing China's technological rise ever more stringently. The initial thrusts under the Trump administration have taken on a markedly different character under the Biden administration. But with each new sanctions step, whether from the U.S. or Chinese side, the negative side effects and dependencies also become clearer. The fact that these are partly accepted reveals China’s willingness to decouple. However, this is not possible in all domains, as China's continued courting of Western capital shows. [27]

We do not expect the conflict to de-escalate anytime soon, and many companies seem to think similarly. They may fear further Western or Chinese sanctions and are either scaling back their involvement in China or trying to separate their activities in China (including Hong Kong SAR) from the parent company. Even if there are individual beneficiaries of the conflict on both sides, the increase in trade barriers is likely to have a negative impact on global growth.

4.2 How important is China's economy for the rest of the world?

In the ongoing disputes between China and the U.S., something often forgotten is that the main protagonists of the global trade dispute are both far less dependent on world trade than, for example, Europe, Japan or many developing countries. Exports account for less than 20% of China's GDP and only a little over 10% of the U.S. GDP, but almost half of Germany's GDP. A process of deglobalization, regionalization, unbundling, or risk diversification – whatever one wants to call it – suggests global trade is likely to become less important as a share of the world GDP. China seems to have less of a problem with this than many other countries. Strategically it would like to further reduce its dependence on other countries and concentrate on developing its domestic economy. It has also addressed the supply of important raw materials ahead of time. The West, on the other hand, is highly dependent on China for many raw materials, especially those that are important for new energies, and on the Chinese consumer. Among the OECD, Germany has the economy that is by far the most interdependent with China. According to calculations by the Economist,[28] exports of goods and services to China by German subsidiaries, plus the revenues generated by German subsidiary companies' earnings in China account for almost 10% of German GDP. For the U.S. the figure is less than 4%.

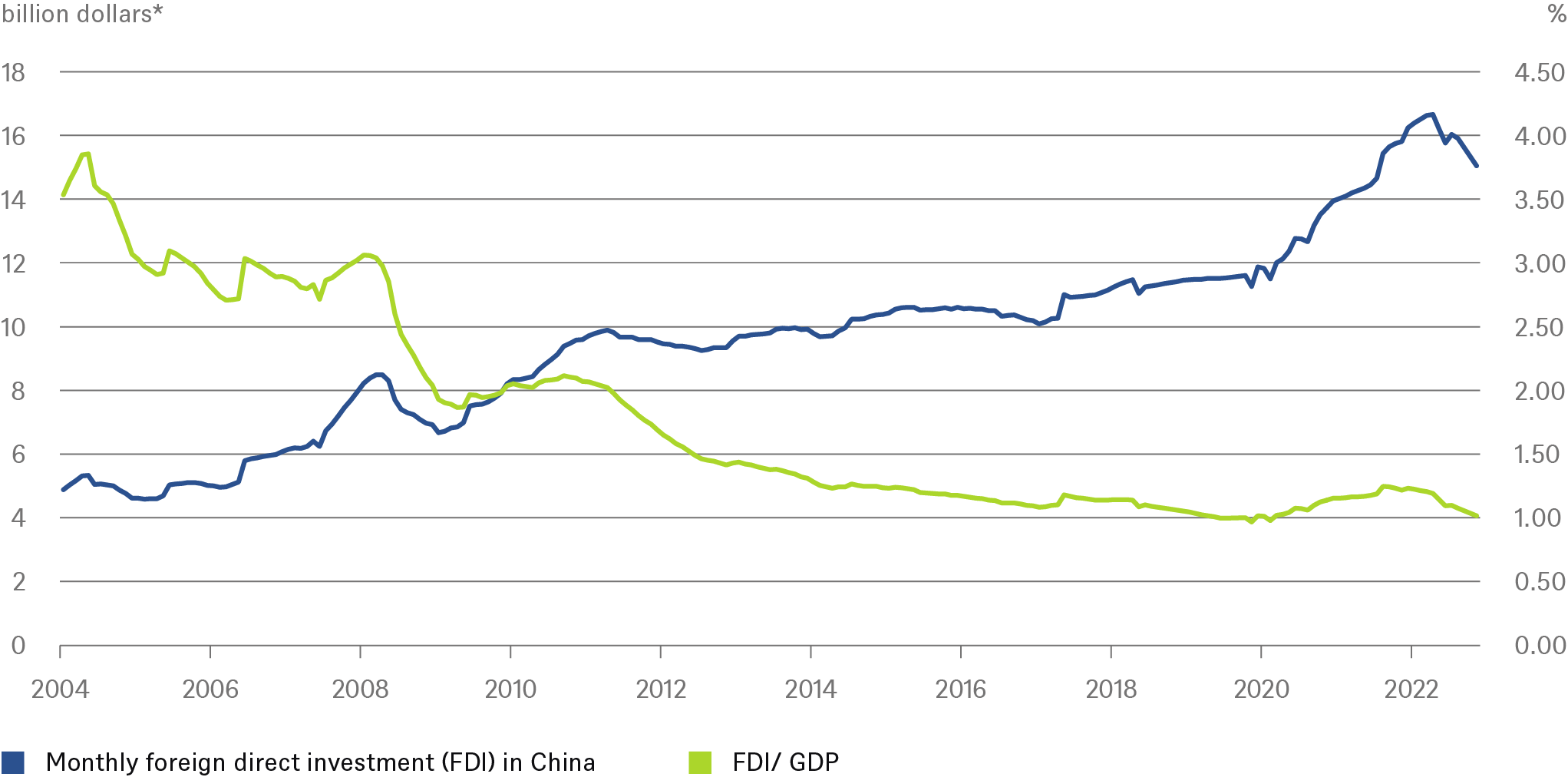

As the U.S.-China conflict has intensified, however, direct investment by the West in China has also declined sharply.

Foreign direct investment in China: normalization or trend reversal?

5 / Not a cycle like any other

In our opinion, China's economy will grow by 4.5-5% this year and next, a level many other countries would certainly be happy about. Nevertheless, it is unmistakable that China is currently struggling with challenges that go beyond cyclical weaknesses. In particular, the real estate sector is in a correction phase that could last for some time and, given the importance of this sector for private households, could also weigh on consumer sentiment for a long time. Linked to this, municipal finances and parts of the financial market are delicately poised. In addition, there are other challenges such as demographics and the chill between China and many of its Western trade partners, as both sides seek to distance themselves. However, in our view, the negative reporting is currently gaining too much momentum. China's strengths in many future-oriented sectors are being overlooked, as well as the government's will to press ahead with structural reforms. This includes, in particular, strengthening private enterprises and supporting strategically important sectors and the municipalities. This will take time. But the quicker ‘solution’ of another debt-financed stimulus package would not be sustainable. However, we believe that the necessary pragmatism, a large domestic market and overall lower than generally perceived dependence on foreign countries will provide in the long run the means to prevent a sharp economic slowdown.